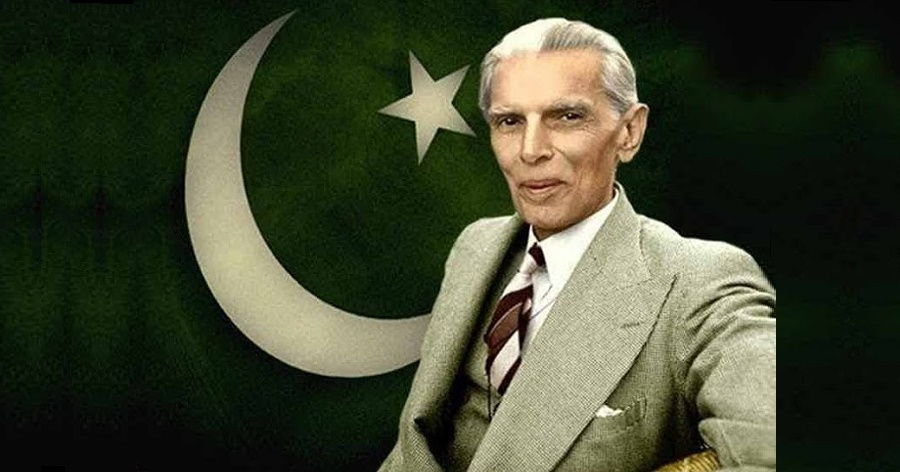

After Jinnah’s death, with no national leader holding the country together, and with a threadbare state, a void opened up in Pakistan. This void has been filled by both civilian and military rulers who, in the absence of a national identity, have advanced their own competing visions of the state ever since. Religious groups along with civilian and military governments have sought to repackage Jinnah as an Islamic leader in order to increase support and legitimacy amongst Pakistani society and to match their anti-India rhetoric. Not only has there been an attempt to create a new identity, but there has been a concerted effort to downplay and distort Pakistan’s history and Jinnah’s vision. As the New York Times reported from Islamabad in the 1970s, Islamization and appeals to Islam are “a form of therapy to resolve a longstanding national crisis of identity.”

After Jinnah’s death, with no national leader holding the country together, and with a threadbare state, a void opened up in Pakistan. This void has been filled by both civilian and military rulers who, in the absence of a national identity, have advanced their own competing visions of the state ever since. Religious groups along with civilian and military governments have sought to repackage Jinnah as an Islamic leader in order to increase support and legitimacy amongst Pakistani society and to match their anti-India rhetoric. Not only has there been an attempt to create a new identity, but there has been a concerted effort to downplay and distort Pakistan’s history and Jinnah’s vision. As the New York Times reported from Islamabad in the 1970s, Islamization and appeals to Islam are “a form of therapy to resolve a longstanding national crisis of identity.”

This “therapy” received its fullest expression during the 1970s under the military rule of General Zia-ul-Haq. General Zia, who had come to power after overthrowing Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto of the Pakistan. Murders in 2011 of Shahbaz Bhatti, first federal minister for minority affairs, and Salmaan Taseer, governor of Punjab. Both were fierce opponents of the country’s blasphemy laws, which are a source of discrimination against minorities; these laws were enacted under the rule of Zia-ul-Haq during the 1980s.

Yet it was not simply the passing of laws that would define Pakistan’s identity along religious lines. Zia recognized that in order to undercut opposition to his rule by the mainstream political parties in Pakistan he needed the support of the religious far right. He thus embarked on a wholesale program of Islamization, telling a BBC reporter in an interview in April 1978 that he had a mission to “purify and cleanse Pakistan.”

Any assessment of why liberal democracy has not taken root in Pakistan cannot go without mention of the overall role played by the powerful military in Pakistan. Pakistan has been ruled by its powerful military for half of its 69 years. The seeds of democracy in this fragile state never really had the chance to grow. Unlike its neighbor India, where the army has confined itself to a strictly military role, the Pakistani generals have been far too eager to depose elected governments at will, imposing martial law and shoring up their own position. The army, as the strongest and most organized institution following independence, was able to step in and fill the void.

The invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviet army in 1979 helped the unpopular dictator Zia ul Haq to strengthen his power. The Western countries were in need of a strong army man who had not to listen to any civil government. During this war from 1979 to 1989 Zia ul Haq got huge support from the West – financially and militarily. From all over the world Islamic fighters were invited to take part in the Jihad against the Russian Communists. During this period of time Zia introduced the Islamic Sharia law and the civil society was oppressed in the worst manner. For the first time in Pakistani history the religious fundamentalist became influential and powerful – a deathly power which till today they are not willing to give up!

Violation of Religious Freedom

Already under Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto religious minorities were political victims. In 1974 the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community was declared as a Non-Muslim Minority. Ahmadi Muslims were not allowed to call themselves “Muslims”. It was forbidden to use Islamic expressions such as Islamic greeting or the call for prayer. Even the expression for “mosque” was not allowed to be used for their place of worship. Now every Ahmadi who calls himself Muslim or express his religious feelings has to be punished with jail of three to ten years and a fine.

1986 the Blasphemy law was introduced by the dictator. This law which was meant against Ahmadis is also used today specifically against Christian minorities and critical citizens who dare to raise their voice against injustice. Anyone who defies the Holy Quran will be punished with life imprisonment. Anyone who uses derogatory remarks against the Holy Prophet Muhammad will be sentenced to death.

The changes in legislation relating to religious offences have contributed to an atmosphere of human rights violation and religious intolerance in Pakistan in which violence against members of religious minorities has significantly increased. Often personal conflicts result in a religious accusation with enormous consequences for the accused. Many a time Ahmadis and Christians are killed for no crime and the state is ignoring the criminal offence. In the Pakistani media Ahmadis are declared openly as that they ought to be killed.

In its 2020 World Watch List report, the international NGO Open Doors listed Pakistan, noting that Christians face “extreme persecution in every area of their lives, with converts from Islam facing the highest levels.” According to Open Doors, all Christians in the country “are considered second-class citizens, inferior to Muslims.” The NGO stated Christians are often given jobs “perceived as low, dirty and dishonorable, and can even be victims of bonded labor.” The NGO also said that Christian girls in the country were increasingly “at risk of abduction and rape, often forced to marry their attackers and coerced into converting to Islam.”

Perpetrators of societal violence and abuses against religious minorities often faced no legal consequences due to a lack of follow-through by law enforcement, bribes offered by the accused, and pressure on victims to drop cases. Legal experts and NGOs continued to state that the full legal framework for minority rights remained unclear. Members of religious minority communities said there continued to be an inconsistent application of laws safeguarding minority rights and enforcement of protections of religious minorities at both the federal and provincial levels by the Ministry of Law and Justice, the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Human Rights. Religious minority community members also stated the government was inconsistent in safeguarding against societal discrimination and neglect, and that official discrimination against Christians, Hindus, Sikhs, and Ahmadi Muslims persisted to varying degrees, with Ahmadi Muslims experiencing the worst treatment.

Freedom of Press

In 2020, Pakistan’s press freedom rank dropped to 145 out of 180 countries in the Press Freedom Index, an annual ranking of countries published by Reporters Without Borders (RWB), an international non-governmental organization dedicated to safeguard the right to freedom of information. The Pakistan’s global index rank was declined for several issues such as killings of journalists, restrictions imposed on news media, withdrawal of government ads, threats, harassment, violation of independent journalism, detention, abduction, and frivolous lawsuits against journalists.

The Council of Pakistan Newspaper Editors, an organization dedicated to safeguards of journalists argued Pakistan’s direct and self-censorship and state-sponsored hostility towards independent journalists working in the country. In the recent years (around 2018 or 2019), seven journalists were killed while fifteen others were injured in different violent incidents. In Pakistan, sixty journalists were allegedly charged under Anti-Terrorism Act. The government, however, cited the issue with the country’s law and order.

Women’s Rights

Violence against women and girls-including rape, so-called honor killings, acid attacks, domestic violence, and forced marriages-remains a serious problem in Pakistan. Human rights activists have estimated that there are about 1,000 honor killings every year. According to media reports, at least 66 women were murdered in Faisalabad District in 2018, the majority in the name of ‘honor’.

Women from minority communities remain more vulnerable to abuse; at least 1,000 girls belonging to Christian and Hindu communities were forced to marry Muslim men every year. The government has done little to eradicate such practices of abuse.

Absence of a Minority Commission

On the 5th of May 2020, the government of Pakistan announced the establishment of a National Commission for Minorities. One can take it as a good gesture. However, serious consideration has not been given to this very important initiative. Since 1990, this kind of ad hoc commission – rather committee – has been established several times without any office, staff, proper mandate and rules of business, and it remained unable to create any positive impact and address minority rights issues. Therefore, it has been a long-standing demand of minority rights activists in Pakistan that a minority rights commission must be established as a statutory body. The said commission can only make its impact if it is constituted through a legislative process as an independent and autonomous commission and provided with adequate resources.

The Supreme Court of Pakistan on 19 June 2014, in its landmark judgement on minority rights ordered that “A National Council for minorities’ rights be constituted. The function of the said Council should inter alia be to monitor the practical realization of the rights and safeguards provided to the minorities under the Constitution and law. The Council should also be mandated to frame policy recommendations for safeguarding and protecting minorities’ rights by the Provincial and Federal Government”.

In the spirit of the principles of United Nations Charter, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and international law, The European Green Party (which works for, strengthening human rights and building a strong, democratic world) and several other international human rights organizations expressed their deep concern about the systematic violation of the rule of law and basic human and democratic rights in Pakistan.

Post a Comment